A short while ago, I had the privilege of being given a tour of the Griffith Institute Archives here in Oxford by its director, Dr. Jaromir Malek. It is one of the most renowned Egyptological archives in the world and it houses among many other things, all the personal papers of Howard Carter, the excavator of the tomb of Tutankhamun.

It seemed almost as chilly as outside when we ventured into the archive room, which is constantly kept at 18 degrees to preserve the fragile documents it houses, but as I glanced up at the famous portrait of Carter, that I’d seen reproduced many times in books, hanging on the wall, I knew that there were many ‘wonderful things’ to come.

You can see them for yourself on the Griffith website here. Also, check out some of the other links I’ve included and take a look at the amazing resources the Griffith has made available online.

Excavation reports are a key feature of the Griffith’s collection. It is important that the archive stores every recorded detail of an excavation, since the importance placed on different archaeological evidence varies over time and it is always possible that new discoveries may be made from old records. The most famous excavation papers at the Excavation reports are a key feature of the Griffith’s collection. It is important that the Griffith are those of Howard Carter and the legendary discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, which have not been fully published yet. However, the Griffith’s remarkable website, entitled ‘Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation’, allows most of these records to be accessed on the internet and offers an in-depth behind the scenes look at the dig. It’s most fortunate that they’re being digitized—the Griffith calculated that if publication continued at the present rate, it would be another 200 years before the records were all made publicly available!

Griffith are those of Howard Carter and the legendary discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, which have not been fully published yet. However, the Griffith’s remarkable website, entitled ‘Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation’, allows most of these records to be accessed on the internet and offers an in-depth behind the scenes look at the dig. It’s most fortunate that they’re being digitized—the Griffith calculated that if publication continued at the present rate, it would be another 200 years before the records were all made publicly available!

Here you can read the transcripts of Carter’s diaries and journals which document everything from the excavator’s thoughts at the initial find, to the tomb’s momentous unveiling, through the long, hard years of actually recording and cataloging all its contents.

The first hint of the discovery of the tomb appears as a simple jotting in Carter’s appointment diary. The small book has Lett’s No. 46 Indian and Colonial Rough Diaries 1922 written on the front and inside, the entry from Saturday, November 4 only has the scribble ‘First steps of tomb found’, indicating Carter’s unawareness of the momentousness of his find. The entry from Sunday, November 5 states, ‘Discovered tomb under tomb of Ramses VI. Investigated same & found seals intact’, by which time Carter would have realized that he was dealing with the thrilling prospect of an unknown but undisturbed tomb.

Most people who are familiar with Egyptology and archeology will be familiar with the legendary words that Carter is said to have uttered upon his first glimpse of the golden treasures of the tomb. Lord Carnarvon is said to have anxiously pressed Carter as to whether he could see anything, to which Carter is said to have replied, ‘Yes, wonderful things.’ However, an entry from a more detailed journal by Carter dating to Sunday, November 26th suggests that those words *might* simply be pure legend, embellished for the purposes of Carter’s book. The entry is beautifully descriptive: ‘It was sometime before one could see, the hot air escaping caused the candle to flicker, but as soon as one’s eyes became accustomed to the glimmer of light the interior of the chamber gradually loomed before one, with its strange and wonderful medley of extraordinary and beautiful objects heaped upon one another. There was naturally short suspense for those present who could not see, when Lord Carnarvon said to me `Can you see anything’. I replied to him Yes, it is wonderful.’

Whatever phrase was actually uttered by Carter, the wonderment he must have experience was fully justified. The treasures of have captivated generations, myself included, and they are one of the main reasons I decided to study Egyptology when I was just six years old. Their breathtaking workmanship was first documented by the professional excavation photographer Harry Burton, whom Carter borrowed from Met with the agreement that the museum could get doubles of the all the negatives. It’s remarkable that Burton achieved such stunning quality photographs simply taking them outside against the backdrop of a white sheet. They don’t take ‘em like they used to anymore. An enormous gallery on the site features all of Burton’s wonderful photographs:

The excavation was a Herculean task, the work of simply clearing the tiny tomb and cataloguing all the objects taking over 5 years, the records consisting of roughly 3000 cards and 2000 photographs. While the excavation is often portrayed as a one-man show starring Howard Carter, a number of the great Egyptologists of the age volunteered their services. Looking at the card records for object number 91, Tutankhamun’s famous throne, Alfred Lucas (best known for his milestone Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries) did restoration work for the object using celluloid cement, and the renowned Sir Alan Gardiner (of Gardiner’s Grammar fame) recorded the inscriptions. Much of the excavation work was aided by Percy Newberry and Arthur Mace.

One of the photos in the collection, taken perhaps by Lord Carnarvon, shows some of these Greats of Egyptology actually luncheoning inside the tomb of Ramesses XI! Seated from left to right in the photo are J. H. Breasted, Harry Burton, Alfred Lucas, Arthur Callender, Arthur Mace, Howard Carter and A. H. Gardiner. This remarkable array of individuals sounds rather more like the gathering that an Egyptologist today might dream up if asked which famous people, dead or alive, one would invite to a dinner party! I’m not sure the Supreme Council of Antiquities in Egypt would allow anyone to have elaborate picnics in any of the tombs anymore though!

Howard Carter himself was much more than just the discoverer of Tutankhamun’s tomb though. He was an incredibly talented artist who came from a family of painters and turned his skills to archaeological illustration. There are numerous drawings and paintings of his in the Griffith Collection. His drawings of the fabulous reliefs from Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el Bahri are impeccably copied down to the last details, including the blocks grid itself. So talented was Carter that he just drew with no visible evidence that he needed to erase and correct his work, nor that he required the aid any drawing tools. My favourite examples of Carter’s work were his small copies of birds and animals depicted on tombs walls and in hieroglyphs, alongside oil sketches of the real life counterparts of these animals. These appeared in the Christmas 1944 edition of the London Illustrated. The talent of the ancient Egyptian artists seems even more striking when one can compare how accurate their detailed observations were. The aleph hieroglyph symbol and Carter’s modern depiction of an Egyptian vulture are incredibly similar, and very beautiful too. Indeed, in my opinion, some of the greatest artistic achievements of the Egyptians are their depictions of the natural world, like the Meidum geese.

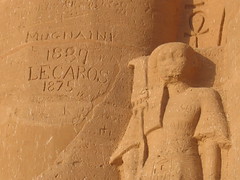

The archive houses many different types of records, including incredibly early ones from travellers in the 19th century. With so many fragile Egyptian buildings eroding away over the past couple of centuries, some completely destroyed by tomb robbers, these 19th century records have become valuable evidence of monuments long since disappeared. Among its collections, the Griffith possesses architectural plans and drawings of Egyptian temples made in 1818-9 by the famous British architect Sir Charles Barry, who designed the Houses of Parliament. Coincidentally, he also designed Highclere castle for the Earl of Carnarvon, whose descendant would go on to fund Howard Carter’s excavations. As I’ve note the differences in the spelling of ancient and modern place place names— for also noted while looking at some of the BM’s archival documents, it’s always fascinating to example, there was a drawing by Barry of the temple of ‘Tentyra’, better known today as Dendera. Other important drawn records dating to the mid-19th century come from the British artist Hoskins and the French architect Hector Horeau. Horeau also recorded the heights to which buildings were sanded up—this is why you can see Victorian graffiti up near the ceilings of some temples, it’s not that they were that acrobatic.

note the differences in the spelling of ancient and modern place place names— for also noted while looking at some of the BM’s archival documents, it’s always fascinating to example, there was a drawing by Barry of the temple of ‘Tentyra’, better known today as Dendera. Other important drawn records dating to the mid-19th century come from the British artist Hoskins and the French architect Hector Horeau. Horeau also recorded the heights to which buildings were sanded up—this is why you can see Victorian graffiti up near the ceilings of some temples, it’s not that they were that acrobatic.

These records preserve times and places that will never exist again, such as Davies’ tracings from a Theban tomb that was never fully published and which is now irreparably damaged. The archive also has drawings made by Lane (known more for his work Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians) using a camera lucida which show obelisks in situ in Egypt that are now in London, New York, and elsewhere.

They also have a collection of squeezes, made by the old-fashioned but remarkably effective method of pressing damp paper against a relief wall to preserve an exact copy of the carved surface, from the serenely sculpted face of a pharaoh right down to the minutest crack. The squeezes from several tombs have been photographed and made available on the archive’s website, for example Theban Tomb TT 57 of Khaemhet, of the reign of Amenophis III.

The Griffith Archive also houses the personal papers of a number of Egyptologists, such as Peet, Gardiner, Cerny, and Gunn. They all wrote a great deal more than they ever published, but it humbles one to realize how much they read and wrote in their lifetimes. Their hieroglyphic writing is beautiful and makes mine look rather like chicken scratchings in comparison!

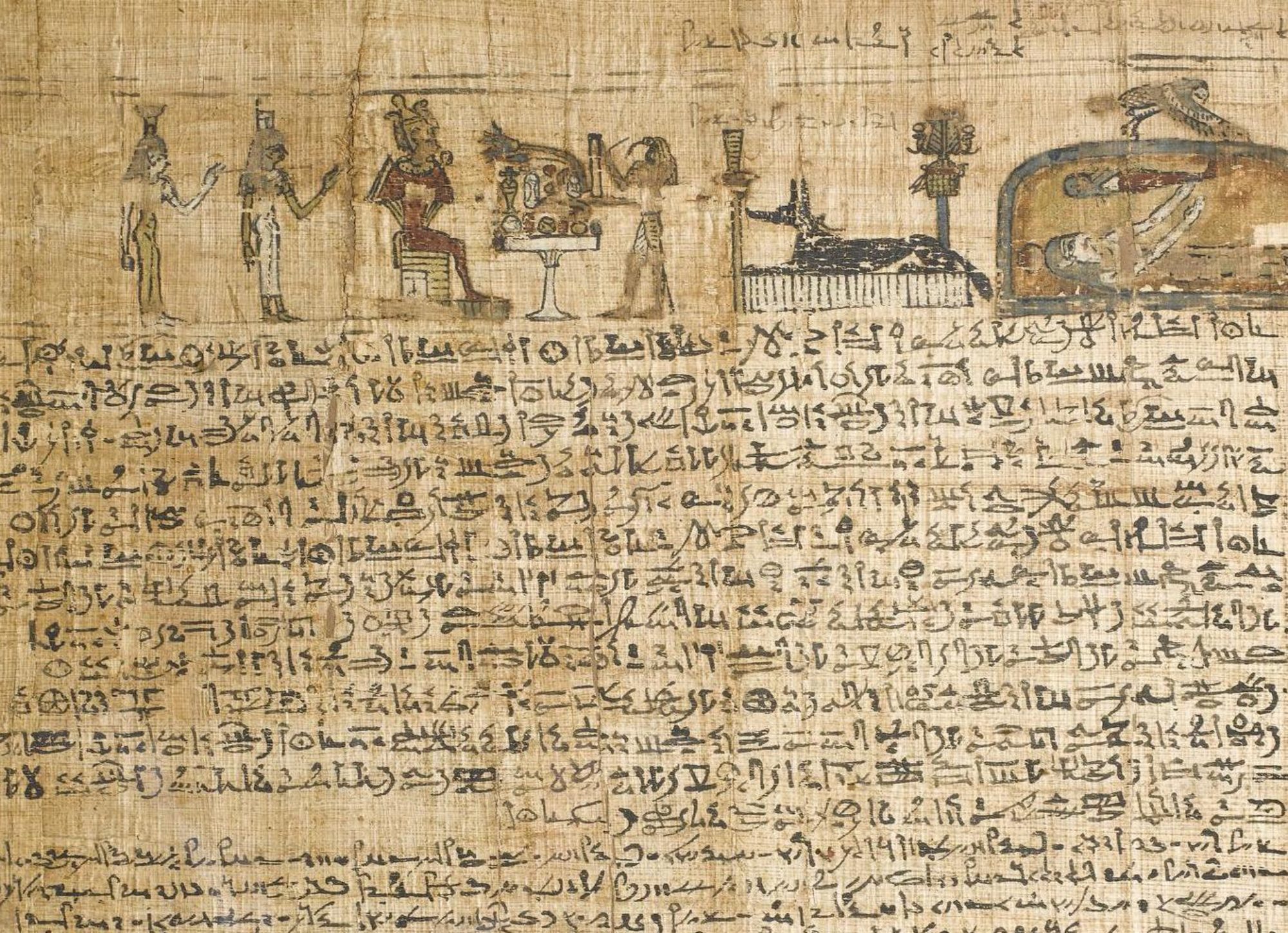

Unfortunately, the archive cannot put the entire vast array of Gardiner’s translations online since apparently some of them have still not been published by the museums that possess the papyri and have first rights to translation publication (though perhaps if they hurried up and actually published them, there wouldn’t be this problem…). Gardiner also wrote an unpublished glossary of the Pyramid Texts, which appeared to be incredibly in depth and correspondingly complicated. I don’t think the Griffith has any immediate plans to publish this at the moment, especially since it sounds like it would confuse anyone who wasn’t Gardiner himself.

Dr. Malek emphasized that the archive conducts its work along the principles of the 4 Cs: collecting, conserving, cataloguing, and communicating. Those principles seem to be serving the archive well, and I have to say that I was incredibly impressed not only by their collection but the care and pride with which its dedicated staff are working to serve the needs of the records and the public.

I will leave you with more of Howard Carter’s compelling description of the opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb:

‘With the light of an electric torch as well as an additional candle we looked in. Our sensations and astonishment are difficult to describe as the better light revealed to us the marvellous collection of treasures: two strange ebony-black effigies of a King, gold sandalled, bearing staff and mace, loomed out from the cloak of darkness; gilded couches in strange forms, lion-headed, Hathor-headed, and beast infernal; exquisitely painted, inlaid, and ornamental caskets; flowers; alabaster vases, some beautifully executed of lotus and papyrus device; strange black shrines with a gilded monster snake appearing from within; quite ordinary looking white chests; finely carved chairs; a golden inlaid throne; a heap of large curious white oviform boxes; beneath our very eyes, on the threshold, a lovely lotiform wishing-cup in translucent alabaster; stools of all shapes and design, of both common and rare materials; and, lastly a confusion of overturned parts of chariots glinting with gold, peering from amongst which was a mannikin. The first impression of which suggested the property-room of an opera of a vanished civilization. Our sensations were bewildering and full of strange emotion. We questioned one another as to the meaning of it all. Was it a tomb or merely a cache? A sealed doorway between the two sentinel statues proved there was more beyond, and with the numerous cartouches bearing the name of Tut.ankh.Amen on most of the objects before us, there was little doubt that there behind was the grave of that Pharaoh.’

I have gratefully used the Griffith’s website to access Carter’s records, notes, and the bewildering collection of photos from

Burton.

Tho if you have enough patience you can eventually find great examples.

What a thrill it must have been to visit there with a personal tour. Your warm description of Carter was pleasant to me.

Thanks for the tour,

René