Most people have heard the famous story about how Rameses the Great’s temple at Abu Simbel was rescued from being submerged entirely by the rising waters of Lake Nasser caused by the Aswan Dam project. The entire temple was dismantled and relocated block by block to higher ground in a project that cost 80 million dollars.

Most people have heard the famous story about how Rameses the Great’s temple at Abu Simbel was rescued from being submerged entirely by the rising waters of Lake Nasser caused by the Aswan Dam project. The entire temple was dismantled and relocated block by block to higher ground in a project that cost 80 million dollars.

Another dam project is now threatening archaeological sites nearby. Further south along the Nile, at the fourth cataract, the Merowe Dam is being built, which will create a lake 2 miles wide and 100 miles long. The dam will flood ancient sites as well as displacing more than 50,000 people. But this time, with no monumental architecture to rescue, archaeologists are simply racing against time to try to uncover as many of the area’s ancient secrets before they are lost forever under the waters.

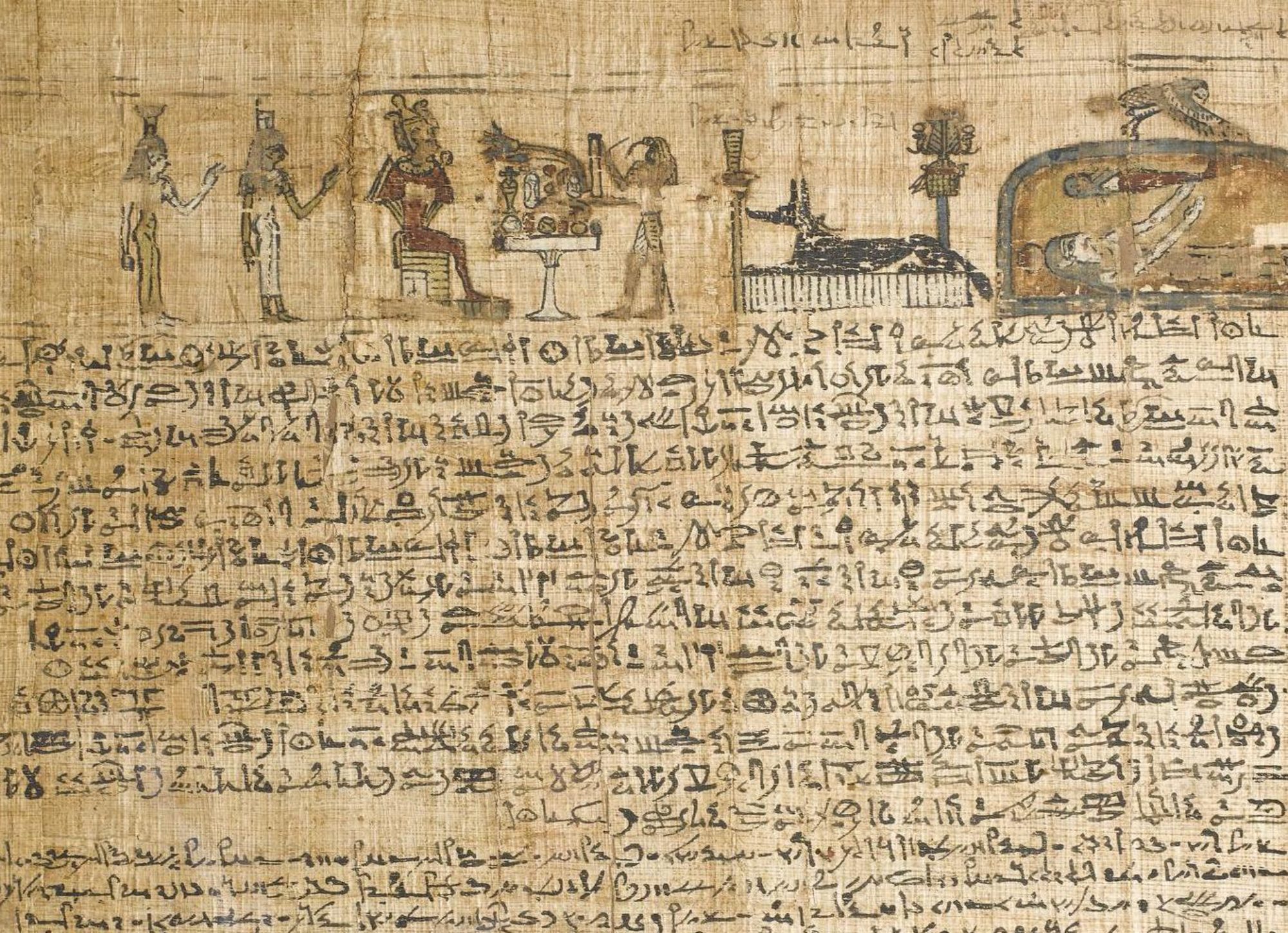

The area under threat was know as the land of Kush, and while we know something about the kingdom indirectly from ancient Egyptian sources, the archeology of the region previously received little attention. It was a land rich in gold and this wealth gave them the power that, despite the lack of a writing system, allowed them to maintain control over a kingdom as much as 750 miles. Archaeologists have found that the extent of the Kushite territory was much larger than previously thought; cemeteries have been excavated and a gold processing centre has been discovered.

While there is only a year left to excavate before the area is flooded, the archaeological salvage attempt has become an international effort. Geoff Emberling, Director of the Oriental Institute Museum in Chicago states, ‘Surveys suggest that there are as many as 2,500 archaeological sites to be investigated in the area. Fortunately, this is an international effort-teams from Sudan, England, Poland, Hungary, Germany and the United States have been working since 1996, with a large increase in the number of archaeologists working in the area since 2003’.

The situation seems to be bringing the kingdom of Kush to the attention of more people as a fascinating society that contributed a great deal to Egypt, whose culture was heavily influenced by their more famous neighbours, but yet was an important kingdom in its own right. Tragically, it comes at the cost of losing something we have only just begun to understand.

was heavily influenced by their more famous neighbours, but yet was an important kingdom in its own right. Tragically, it comes at the cost of losing something we have only just begun to understand.

Andrew Lawler of the Humboldt University Nubian Expedition states, ‘The Fourth Cataract–after a brief emergence into the archaeological limelight–seems destined to slip back into obscurity, this time for eternity’.

It is critical that the western world understand the consequences of the new Meroe dam project . A national

appeal is emminent. My recent book “Nubian Pharaohs and Meroitic Kings : The Kingdom pf Kush ” will give you the immensity of such acultural lost.

Ms Harkless’ book is important, and ranks with Martin Bernal’s monumental ‘Black Athena’ (1987). She and her colleagues rightly refer to Egypt as Kemet, ‘the Black Land’.

In ‘African Exodus’ (1996), Stringer and McKie compare the 1967 discovery of the 130,000 year old male skeleton found beside the River Kibish in Ethiopia with the rediscovery by Alex Haley, author of ‘Roots’ (1976), of his distant Gambian relatives, concluding: ‘He is humanity’s African kin. He is us, and we are him.’

Can it be doubted that civilization radiated out of Africa along the route of the Nile, and that Egypt only became (if I may so phrase it) alienated from these common origins by geographical factors and the inevitable struggle for resources? It is noteworthy that the Egyptians did not base their class relations on racial characteristics (Allen, 2001, p.32). The time has come to expose the propagandist slur of ‘kš _hzt’ and recognise that the preservation of our common archaeological heritage is as much an environmental concern as the maintenance of biodiversity.