It is now two weeks since it was announced that a number of objects were missing from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, and a month has passed since the actual break in when the objects taken. However, even though an official list of missing items was released, because of a lack of photos, inventory numbers, or detailed information, we still don’t actually know precisely what’s missing. It is possible that this information could be valuable in stopping the objects from leaving the country or being sold.

Since the break in, museum staff have been working very hard under difficult circumstances trying to assess the situation, repair broken objects, and search for those that are still missing and I certainly applaud and appreciate their efforts. The museum has now reopened and many of the objects that were damaged are back on display. Dr. Hawass has stated that even the terribly damaged wooden statue of Tutankhamun on a panther has been restored, and press videos show that the Mesehti models from Asyut and the cartonnage of Tujya have also been repaired and are back in their cases. Several of the missing objects have been miraculously recovered, including the Akhenaten masterpiece.

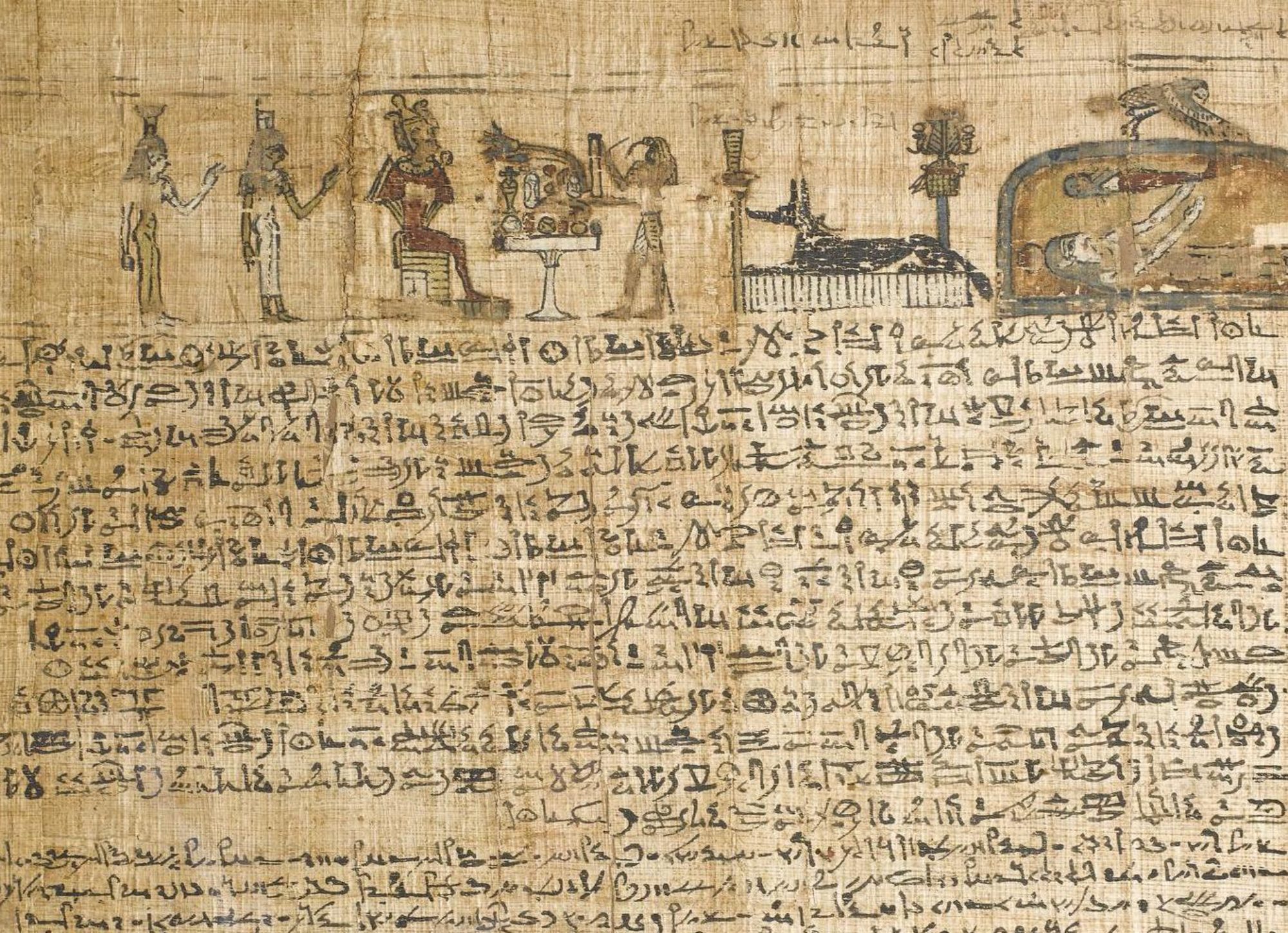

I hope that soon there may be time to release more detailed information and photos of the objects that are missing. As of yet, the statue of Nefertiti that was stolen has still not been identified and we are not sure which Amarna princess head is missing. I have been checking a number of publications for information about these pieces and have still found nothing. The majority of the Amarna princess heads are made of quartzite rather than sandstone, as listed on the inventory of missing items. It doesn’t help though that Borchardt, the probable excavator of the piece, identifies many of the heads as sandstone, though they are now acknowledged to be quartzite. I haven’t been able to find a copy of the original publication that *may* contain this statue in either Oxford or London, so if anyone has access to Ludwig Borchardt’s Ausgrabungen in Tell el Amarna 1912/13 in Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 52, 1913, it would be great if you could check it out!

I understand that the assessment of the collection at the museum is still ongoing and there are also many positive results of recent days to focus on, but if there is a chance that information and photographs of the missing objects could help their recovery, I hope that they can be made available in the near future.

Dr. Hawass’ latest statement says:

The museum’s collections management and documentation team continues to work with the curators to complete their inventory, so that we can finalize the list of missing objects and concentrate on getting everything back as soon as possible.

Unfortunately, there are people saying things that are untrue, and trying to make trouble, and sometimes the media likes to repeat these stories, because they think this will interest the general public. I prefer to ignore these people, and focus on our work. There is much to do to protect our monuments, and this is now, as it has always been, my first priority.

There has been a lot of varied discussion recently about how to assess the antiquities situation in Egypt and what measures might be taken recover and prevent the trade of looted items. With a number of items still missing and sporadic looting attempts continuing, it is certainly worth discussing these issues to consider potential courses of action and ways in which people might help. An article by Dr. Declan Butler in the journal Nature addressed some of these questions.

He noted that Hague Convention outlines measures that could be taken in future to guard against and better assess any threats to sites and museums, while an international assessment mission, like the one carried out in Iraq, has been a suggestion:

The massive destruction of cultural heritage during the Second World War prompted the adoption of the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict in 1954 at The Hague in the Netherlands. Signatories to the Convention pledge to take measures such as creating maps and inventories of cultural heritage, and to set up military units with expertise in archaeology and the protection of key sites and artefacts. In principle, governments and armies should draw up heritage-protection plans during peacetime, which can be activated once a conflict starts…

Rühli hopes that Egypt will call on external experts to form an international mission to assess the damage, and decide what restoration is needed. Such a mission could also assess the security at sites, and how this might be improved. Jan HladÃk, a specialist in cultural heritage at the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), notes there was a similar UNESCO mission during the Iraq War, in 2003. Researchers have also called on law-enforcement agencies and art dealers around the world to look out for stolen Egyptian antiquities.

Rick St. Hilaire, a cultural heritage lawyer, has discussed the possibility of implementing legislation in the United States to protect against objects being imported, enacting an Emergency Protection for Egyptian Cultural Antiquities Act. He also offers practical advice on who to contact for anyone who encounters a potentially looted object or has suspicions. I would be very interested to learn more about possible legislative avenues outside the US as well. There has been some defensive backlash against such legislation from collectors in America, who have accused archaeologists of using the looting in Egypt to try to strengthen restrictions on the import of Egyptian artefacts ‘far and beyond the scope of authority vested under U.S. law’, however this response seems rather reactionary and self-interested.

St. Hilaire has also commented on the need for better information in any efforts to protect Egyptian heritage:

The welfare of the Egyptian people are to be considered first while we continue to monitor cultural property issues. One issue that requires attention is obtaining reliable information. The lack of credible information regarding the theft or looting of cultural objects in Egypt requires resolution, especially since many cultural organizations have called on law enforcement to remain alert. Authorities at the US border cannot be expected to be on heightened alert when there is conflicting information about the extent of looting at archaeological sites or thefts from museums. Egyptians involved with cultural heritage, aided by journalists on the ground, should investigate the extent of damage to cultural heritage in Egypt. Only then can American authorities provide appropriate assistance.

The most effective way of protecting against trade and looting of antiquities is on the ground, through assessment and heightened security. The employees of the new Ministry of Antiquities and the Egyptian people have made an enormous effort to this effect, and the world owes them a debt of gratitude. Again, Egypt has already managed to recover a number of items that were taken from various sites, but presumably assessments are still taking place of what is gone and what damage has been done. Hopefully if any of the archaeologists who work at the sites in question can be of any assistance they will be included in the process.

A recent report on the situation was made by the Blue Shield, and Lee Rosenbaum has posted addressing it and the potential need for further assessment of the antiquities situation there. The Blue Shield report concludes by stating:

It is important to plan further missions in Egypt in the near future, since only a very small portion of areas where damage was reported could be surveilled. It is strongly suggested by the mission that a conference in Egypt should be planned in the near future to analyze the security situation at archaeological sites, on how to deal with emergency situations and how to create contingency plans using the Egyptian example.

Dr. Robert Bianchi, on the Restore + Save group, made the suggestion that a policy allowing photography at museums and sites in Egypt might have helped better assess the looting at the museum and elsewhere. He urges that the policy be revisited. He also suggests that the Egyptian media be given a more active role in issuing antiquities announcements:

If the revolution will truly be bringing a return of power to the people of Egypt then perhaps one of the issues to address is the role of the media. The Egyptian media should be given the exclusive right to be the voice of the antiquities service (in whatever form it will eventually become) rather than hand-picking selected non-Egyptian media outlets for such announcements.

There are a lot of potential avenues that could be taken to try to protect sites and objects both now and in the future, and hopefully Egypt, other governments and international organisations, and Egyptologists can also contribute to this dialogue and future course of action. If you have suggestions, please add your contribution to the comments below!

In other news, a recent statement by Dr. Hawass addressed the subject of protests outside the Ministry of Antiquities, stating that a number of the protestors had apologised and brought flowers and planned job creation would open up 900 new positions in the ministry.

It is worth noting that the UK travel advisory for Egypt has now been lifted, all museums and sites have re-opened, and efforts are being made to encourage visitors and welcome tourists:

Ahram Online reports that security guards and archaeologists managed to thwart an attempt by a gang of thieves to break up and steal a colossal red granite statue of Ramses II from a quarry in Aswan.

There have also been reports from the US Copts association (via Kate) and on the Facebook Restore + Save group of Coptic monasteries being attacked by the army.

In more positive news, there has been a proposal that the burned out National Democrative Party headquarters beside the Egyptian Museum in Cairo be turned into a public garden. It has previously been cited as a potential risk to the museum because of the structural damage it has suffered.

UPDATE 2nd March 1am:

In an interview with the New York Times, Dr. Zahi Hawass, Egypt’s Minister of Antiquities said ‘that his department was unable to protect Egypt’s historic sites and artifacts and that he was considering resigning. In a telephone interview he said that thieves on Monday broke into two warehouses near the pyramids of Giza that held artifacts excavated in the early 20th century. It was not yet clear what had been taken’. He also stated that ‘people had also been caught excavating at night at Abydos, an important archaeological site north of Luxor’.

For further accounts of the break ins at Giza, see the following articles at Al Masry Al Youm and Bloomberg.com.

Also, in an interview with the Prague Post, Miroslav Barta discusses the possible break in at the Czech storehouse at Abusir.

Thanks again for a very detailed, informative post. I appreciate knowing what’s happening in Egypt, and consider your blog to be a very valuable source of solid information.

Excellent posts and very much appreciated by all.

We have the volume of Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 52 in the Watson Library at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and several princess heads are illustrated; one is said to be of “Violetter Sandstein,” others of “brauner” or “bremalter” sandstone. The “violet sandstone” head might, but also might not, be one of the heads in the linked post’s image from 1936, but I can’t imagine how to figure out whether any of them is the missing head. Perhaps a real Egyptologist (and German reader) could do better, but without some more clues to the missing object, it’s hard to know how.

Thanks for your careful reporting.