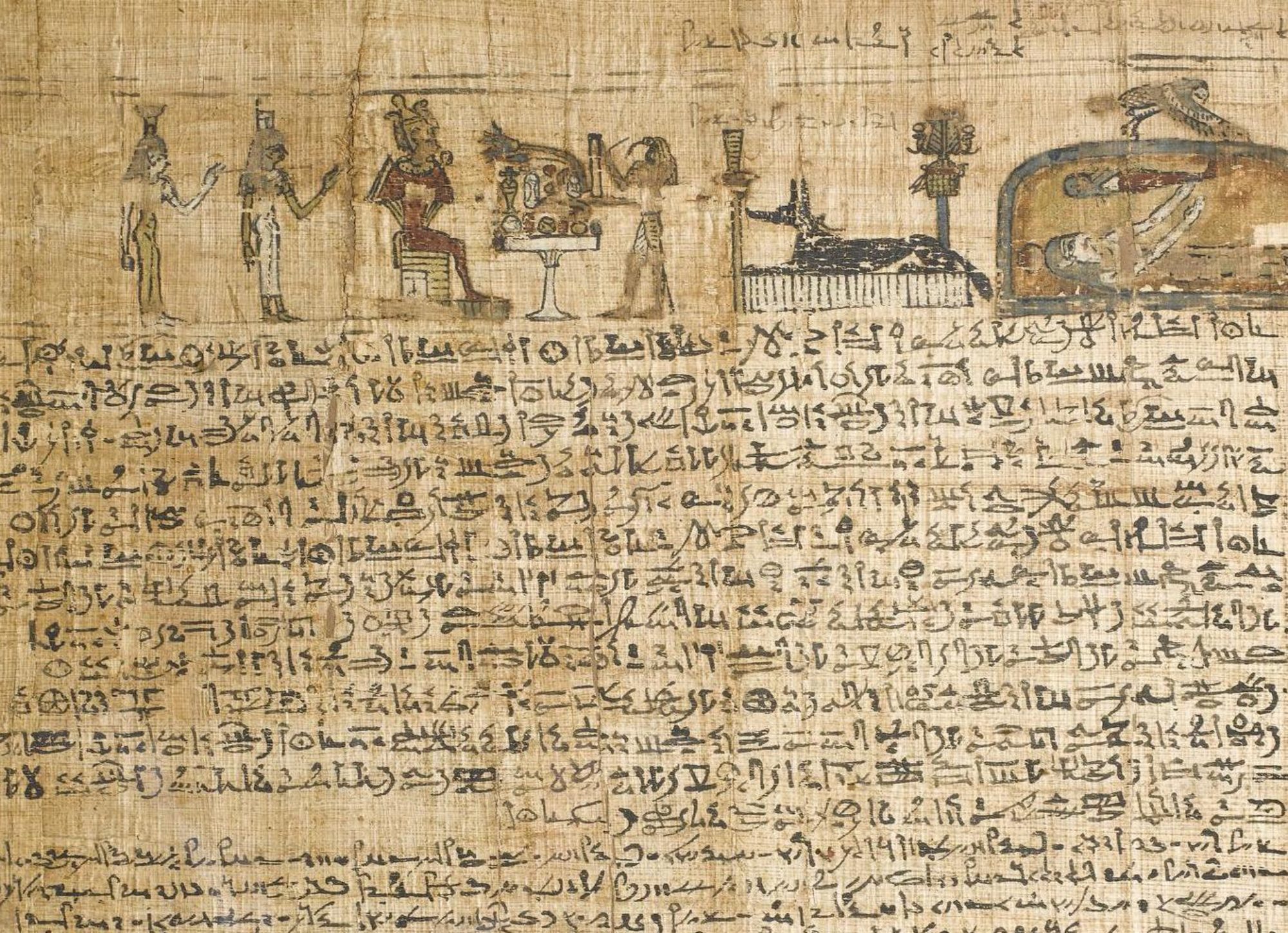

As most of you’ll have noticed from the Google doodle posted today, May 9th 2012 is the 138th birthday of Howard Carter, the archaeologist celebrated for discovering the tomb of Tutankhamun. While many know him for that achievement, his original training was as an artist and some of his most notable work may actually be the incredible artistic records he produced, some of which may be viewed here.

While other Egyptologists such as Champollion and Petrie were famed for their scholarly advances, Carter superseded them in the public imagination with a discovery borne out of perseverance and a bit of luck. The discovery undeniably advanced our understanding of ancient Egypt massively overnight, and the vast range of objects in such a hastily assembled, minor king’s tomb is but a hint of what would have been discovered in the tombs of the greatest kings of the New Kingdom. The discovery has inspired future generations of Egyptologists and archaeologists, and the objects themselves have contributed to our understanding of everything from ancient Egyptian flora and clothing to boats and furniture.

Recording and removing the objects from the tomb took Carter 10 years, and with this sheer volume of objects, the finds are still being published today. It has been estimated that if publication continues at the present rate, it will be another 200 years before thorough records and studies of the finds are made! Luckily the Griffith Institute Archives in Oxford, which I’ve written about previously more fully here, has digitized the thousands of record cards, photographs, and diaries from the excavation and made them publicly available online. This important endeavour has taken fifteen years and I highly recommend exploring the site if you haven’t already!

It may be that the populist appeal of the tomb’s treasures and often sensationalist slant to the endless media interest have put off some scholars from working more on the Tutankhamun objects. Nevertheless, research continues today on the objects, and in addition to Joyce Tyldesley’s recently published general interest book, publications in the past few years include works on the various chairs and seating furniture found in the tomb, Tutankhamun’s footwear, and DNA testing performed on his mummy. Further research on the chariots found in Tutankhamun’s tomb will be presented at the First International Chariot Conference in December later this year.

Despite these advances, last year, the legacy of Carter’s discovery was threatened by the looting of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The following video of a powerpoint presentation from the second seminar of the World Wide Archaeology Commission in cooperation with the Egyptian Museum shows which museum cases were broken into and, using before and after photos, demonstrates the extent of the damage to the objects, the restoration process, and the final result. Although some of the stolen Tutankhamun objects were recovered, many remain missing today.

Archaeology is fundamentally a destructive process and it is only through keeping thorough records that we can hope to make sense of what we discover about our past. Howard Carter’s initial involvement in Lord Carnarvon’s search for Tutankhamun resulted from his recommendation as an assistant to ensure proper archaeological recording. The best way to protect and preserve the objects of Tutankhamun’s tomb for the future is to continue to pursue their careful study and publication and share our knowledge with all.