A recent survey of UNESCO World Heritage Sites rated the Giza Pyramids as one of the 25 most poorly maintained. There are extensive plans to greatly improve the Giza Plateau, but they are unlikely to be popular with local inhabitants who make their living there, since a key part is removing them from the site. The issue of protecting and developing archaeological sites while balancing the needs of Egyptians, archaeologists, and tourists has been much in the news lately, so I thought I’d offer some of my thoughts about the negative impact of local activity at archaeological sites and the subsequent relocation of local populations, like at Gurna, Luxor, and Giza.

Gurna

The story about bulldozers being brought into the village of Gurna near the Valley of the Kings back at the beginning of December to forcibly remove roughly 3,200 households reluctant to leave was quite widely reported. These people were living directly amongst the Theban Tombs of the Nobles, mostly dating to the 18th Dynasty.

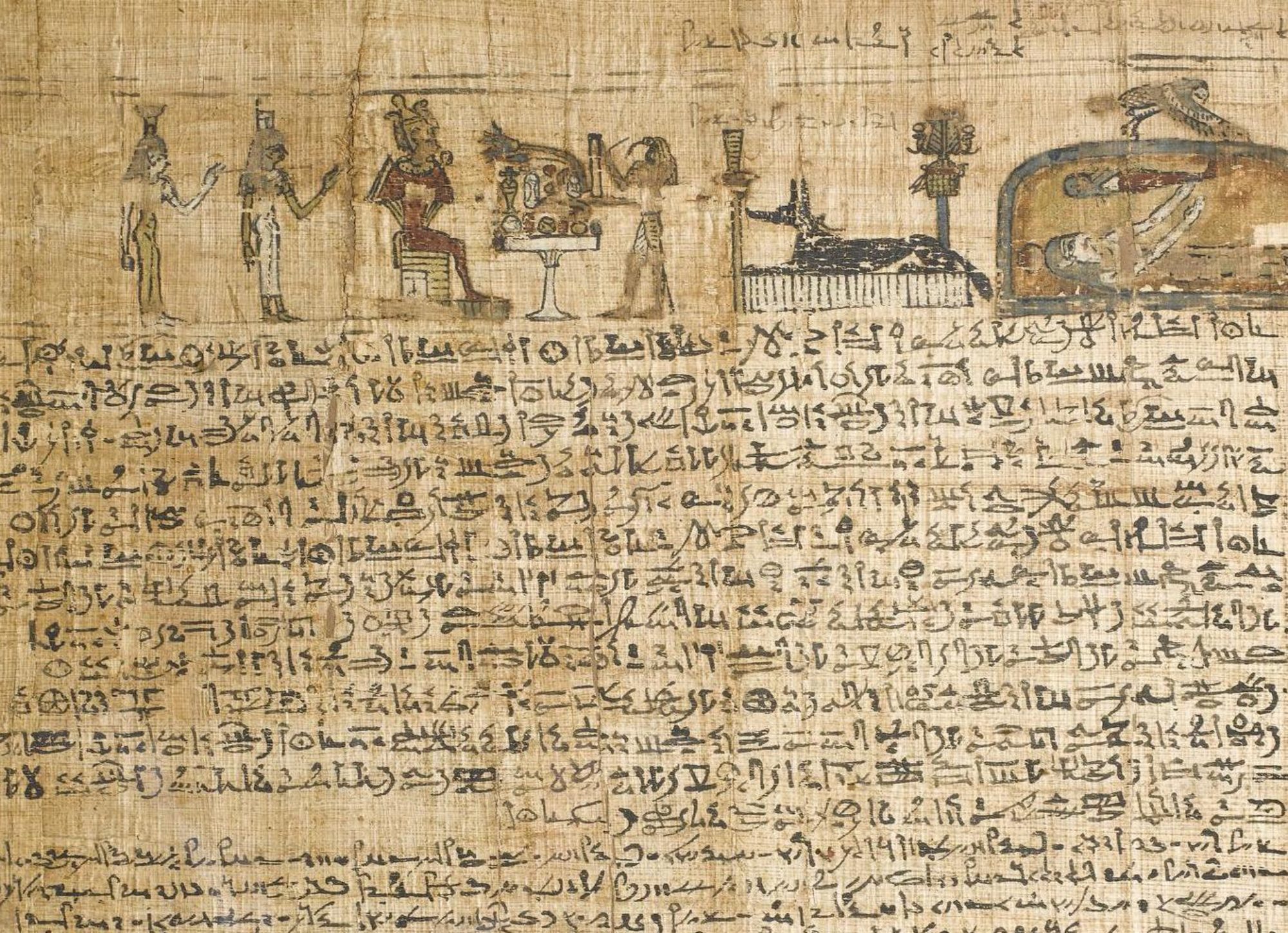

The tombs in question contain some of the most exquisite artwork in the world. While the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings may be grander, the decoration in the tombs of the nobles is still incredibly skilled with the added charm of the subject matter of everyday life. Rather than taking my word for it, take a look at these photos from the tombs of Sennefer, Ramose, and Menna.

However, the situation in the village of Gurna has made it extremely difficult to visit them. When I visited last year in December, it was practically deserted compared to the throngs of tourists overflowing the nearby Valley of the Kings. Likely this is partially because the site is far from accessible. Just trying to find particular tombs hidden amongst the minefield of houses, souvenir shops, goats, dogs, children, rubbish, and would-be tour guides, was challenging.

While removing the buildings and people from on top of these tombs is unquestionably the best measure to preserve and protect them, it raises many issues about the rights of the local people who have lived there all their lives. Many of them descendents of the 19th century tomb-robbers of Gurna, they owe their livelihoods and their own unique culture to their relationship with the tombs and tourists.

Their story was immortalised in Shadi Abdel-Salam’s epic film, Al-Mumia (Night of Counting the Years), in which a conflicted young villager struggles with the dilemma of whether to follow the tradition that feeds his family by selling the treasures of the hidden tombs or to preserve their ancient history by handing them over to the government. A captivating article by Fatemah Farag in the Cairo newspaper Al-Ahram further describes the desire of both locals and outsiders to preserve the unique history and heritage of the people of the mountain.

In the end, the eviction of the Gurnawis boils down to yet another chapter in the age-old conflict between Western values and the interests of modern Egyptians. This particular struggle at Gurna has been ongoing since the government’s first unsuccessful attempt to remove the villagers in 1948. It’s a uncomfortable situation when the dead are given priority over the living, the needs of Egyptologists and foreign tourists over the lives of the local people.

I certainly have mixed feelings over the issue. But while it is easy to express pity and guilt over the sidelining of the villagers and their needs, as a tourist and an Egyptologist I can’t deny that I wouldn’t prefer to be able to visit the Tombs of the Nobles without being stalked by wizened old men unnecessarily trying to read names in hieroglyphs for me, while repeatedly making the same unamusing wisecrack about Canada and demanding baksheeh (tips).

For the sake of the tombs themselves and their beautiful decorations, this is what needed to be done, and should have been done properly back in 1948 or even before, but it is unfortunate that a better compromise wasn’t made with the people who had been living there for generations. Since the development of the site will most certainly increase tourist revenue considerably, the government really should have stepped up and provided more suitable accommodation for the people they were forcibly removing. It’s not only in Gurna that this sort of thing is happening though…

Luxor

There are plans to restore the ancient, sphinx-lined processional way linking the great temples of Karnak and Luxor, the beginning of which can be seen in this photo. Stretching over three kilometers, the planned road would cut a 60- to 70-meter-wide swath right through a largely residential area of modern Luxor. The ceremonial route was the focal point of the immense Opet festival, in which the king and the sacred statues of Amun and his divine family travelled from his temple at Karnak to the temple of Luxor.

The planned road will stretch over three kilometers and cut a 60- to 70-meter-wide swath right through a largely residential area of the modern city. The people who are unfortunate enough to be living in the wrong place will be moved to apartments in a proposed new city that is to be built on the edge of Luxor.

When I was in Luxor, I met a shopkeeper who was one of the people who was going to be moved. While he was glad that he wasn’t just being turned out and would at least receive a new home in compensation, he was still unhappy about the situation in general and regretted being forced to leave.

In this case though, the eviction is not for the sake of protection of monuments or the archaeology, but purely to increase tourist profits. It seems a bit strange that this is being done when there are so many other places where urban settlement makes excavation of important archaeological sites impossible. I hope at least the end results will be spectacular enough to somewhat justify the expense of the people who lived there.

The Giza Pyramids

An eviction of a different sort is planned for the site of the famous Pyramids at the Giza Plateau. The master plan for the development of the site will prevent access to the illegal vendors and touts that overrun the site, in addition to cutting off vehicular access and removing all the inappropriate modern developments to the plateau. And perhaps just in time too. In a recent review of 94 major UNESCO World Heritage sites by George Washington University in cooperation with National Geographic, Egyptian sites are all among the bottom-25 of the list, the Pyramids ranked as the lowest, receiving only 50 out of a possible 100 points.

Comments made by the panelists document the same dissatisfaction that most visitors to the Pyramids express:

‘Of all the major sites in the world, this is the one where the most people seem to come away disappointed. The slums march right up to the base of the pyramids, the smog gets worse every year, and the touts are relentless. Not a pleasant experience for visitors.’

‘Poor signage and interpretation. Lots of hassling of tourists—difficult to look at the structures for a minute without being offered something.’

My own impressions were the same when I visited the Pyramids. I was appalled by the way tourists were constantly hounded by trinket-sellers and camel ride operators, with not a moment’s peace to spend in quiet contemplation of the world’s most magnificent monumental structures. Everywhere we went we trailed an entourage of Egyptians pressing everything from bookmarks to postcards on us as we kept up a constant chorus of ‘La, la, la!’ (‘No, no, no!). I saw one girl who was being harassed actually break down in despairing, outraged tears and fling her water bottle at her unwanted pursuers. Men soliciting tips in exchange for unofficial tours outright lied to my friends and I about the opening times of the Great Pyramid in an attempt to lure us away from it. They told us all sorts of incorrect information about the queens’ pyramids and claimed that they would show us mummies in them. There most certainly aren’t any mummies in the pyramids anymore. It was incredibly disappointing that an experience that I had dreamed of all my life was so horribly marred by the situation there.

I think that change is desperately needed at the Pyramids and the master plan for the Giza Plateau is good overall, it is notable that it is the international community that benefits yet again rather than the local population. Hopefully though, while the plan will adversely affect some of the illegal workers on the site, overall the local community will community will benefit from increases in tourism. My friend Dr. Paul Gardener commented on the imbalance in the Giza plan in his thesis on heritage management strategies:

‘While the plan doesn’t seem to be very balanced,…given that this site is of such special archaeological and historic significance, we might decide that, in this case, the principle of sustainability is more important because of the very strong argument in favour of conserving this unique set of ancient monuments for as long as possible.’

But ‘the site’s high economic and social value for the local community will be severely crushed when their free access and use of the site is restricted… Instead, this master plan will promote the exclusive use of the plateau as a well ordered, Western space. This may sharpen the divide and prevent interaction between the visiting tourists and the host community…

The politicians, tour operators, international tourists and academics gain. They would inherit a site that is purposefully managed for their professional and leisure interests. The local entrepreneurs and unofficial tourist service providers and residents of Cairo would lose since their access to and use of the site would be restricted and controlled. This lack of equity of benefits for the stakeholders raises the question of to whom does the ancient site of Giza principally belong: the rich and well educated international community or the poor local community?’

Biased as I am, I certainly don’t have the answer, but I believe that Giza belongs to posterity and that while the Egyptians should certainly benefit from the Pyramids, it is the responsibility of us all to preserve their heritage.

Reference:

Gardener, P. (2006). Reusing Roman Monuments in Arles and Nimes: An Evaluation of Heritage Management Strategies in Local Government. Oxford, University of Oxford.