It may have seemed just a typical grey winter’s day in London yesterday, but in a small room on Great Russell Street some very different scenes were unfolding. Beautifully attired men and women gathered for a banquet, watching musicians and dancers, with huge vats of wine wreathed with floral garlands and tables heavily laden with a rich array of food and bouquets of exotic flowers. Nearby, a family was out together on the water for a pleasure cruise and hunting trip, enjoying the beauties of nature as flocks of brightly coloured birds, fish, and butterflies rose in great swirls of movement around them.

Yesterday at the British Museum, the tomb paintings of Nebamun, some of the most famous images in Egyptian art, were finally unveiled again in a new permanent gallery after 10 years of conservation.

On Tuesday night I attended a reception for the opening of the gallery. It was a moment that many people worked long and hard for, from the conservators to the museum assistants, and not least its curator Richard Parkinson. And it was a triumph. It is not only the extraordinary paintings, beautifully restored, that make the gallery such a success–the remarkable reorganization of their display and the design of the gallery completely transforms the way visitors will interact with the museum’s Egyptian collection.

In the past, hundreds of monumental stone sculptures and crowd-thrilling mummies have dominated the museum’s displays, but now visitors will have a chance to see the Egyptians as ordinary people just like them, filled with hopes, fears, and desires. The design of the gallery with its lovely limestone panelling conveys the feeling of the actual tomb. The gallery is small enough to give it a feeling of intimacy, without feeling confined–I only hope it can withstand the extent of the crowds that often swarm through the museum.

Before the paintings were removed from display for conservation purposes (a complex process that involved everything from removing harmful plaster of paris backing to reversing Victorian ‘corrections’ made to the paintings!), they were previously displayed in frames, arranged along the wall as if in an art gallery. The paintings are now arranged according to their likely original locations in the tomb, exhibited on a slightly reclining angle to protect them. Their new integrated display allows the tomb’s message to speak, rather than imposing a Western concept of art on them. It allows the paintings to be exhibited in a way that conveys a sense of their original connectedness, giving a sense of the original unified design space–a place commemorating Nebamun, where friends and family could visit and bring offerings for his spirit in the afterlife. To further convey the sense of what the tomb would have been like, there is video display of a digital recreation of the site and tomb interior, which should also be online soon in an interactive version.

Another remarkable touch is that if you look through the cases that display daily life objects from that era, you can see through to the paintings hanging beyond and actually see the painted depictions of incredibly similar items being used by Nebamun, his friends, family, and workers. Amazingly the cases containing the paintings themselves use non-reflective glass so there’s no glare to impede your view- it almost feels like the glass isn’t there at all.

Several people spoke during the evening, including the director of the museum and the Times Briton of the Year, Neil MacGregor, who spoke amongst other things about how the gallery would bring visitors in touch with real ancient Egyptian people, for example the amazingly preserved loaf of bread that still bears the fingerprints of the baker.

Sir Ronald Cohen, known as the father of venture capitalism, who generously contributed to the funding of the gallery. His personal involvement in the region is an extraordinary story. Cohen is the British son of a Syrian Jew and was born in Egypt. In 1998, he was presented with Israel’s highest tribute, the Jubilee award, as “one of the visionaries who have done the most to facilitate Israel’s integration into the global economy”, and then in 2005 he established the Portland Trust to help the Palestinians “build up a powerful economy . . . based on a deep level of interdependence with Israel”. He spoke very eloquently about naming it in honour of his father Michael Cohen, a lovely gesture that echoes the image of Nebamun being honoured by his son.

The new Egyptian ambassador to Britain, who officially opened the gallery, used his speech to highlight parallels between the current situation in the Middle East and the Amarna correspondence, written shortly after Nebamun’s life, in which chieftains in the region of Palestine wrote to the Egyptian pharaoh asking for help defending themselves against attacking forces. During the course of the evening, I also spotted Cherie Blair eagerly looking around the gallery.

If you’d like a little taster of what to expect, there are some great videos featuring footage of the paintings and the new gallery itself and interviews with Dr. Richard Parkinson, the Egyptologist who masterminded the whole project at the Telegraph and the Times.

Much has been written about the gallery over the past couple of weeks. One of the most informative is a wonderful piece in the Guardian Weekly in Dr. Parkinson’s own words. There have been numerous other very positive and well-written articles about the gallery, all of which I’ve found interesting reading, for example in the Guardian, and also from an Egyptian perspective,

Over the past few years, I myself was very lucky to have the amazing opportunity to work the paintings over the summer months that I spent as a curatorial intern at the British Museum. When I was a teenager, I actually had a poster of the painting of Nebamun fowling in the marshes in my room, so needless to say it was an extraordinary experience. One of the things I was able to do was contributing to the descriptions of the paintings in Chapter Three of the book ‘The Painted Tomb-Chapel of Nebamun: Masterpieces of ancient Egyptian art in the British Museum‘.

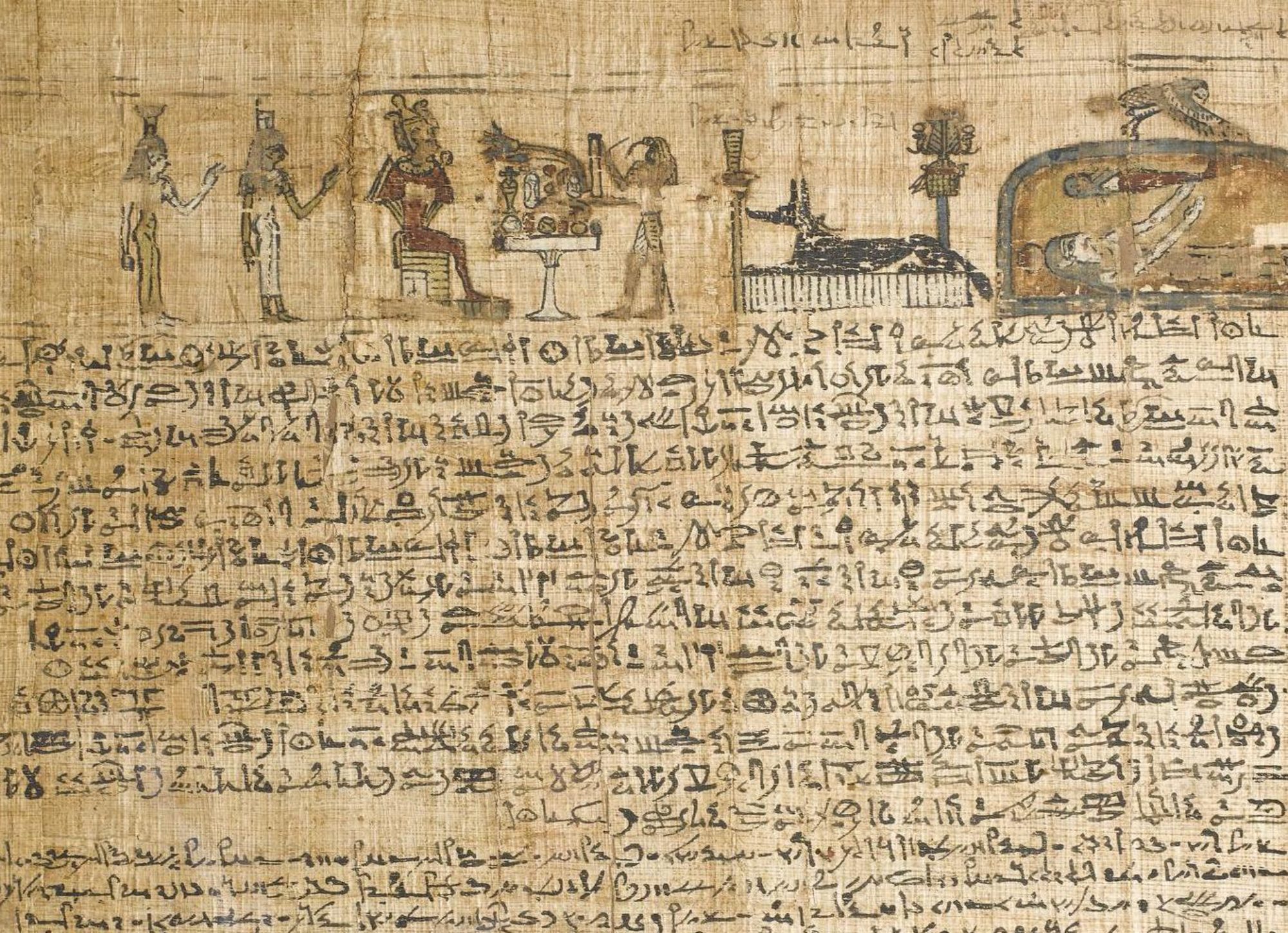

The Nebamun tomb paintings in storage

For this task, my fellow intern Ally and I sat in front of them for hours, examining them in minute detail and considering the individual brushstrokes. Every time I looked at them, a new detail would catch my eye. The paintings are incredibly skillfully produced, exhibiting numerous delicate techniques used to produce various textures and effects. But at the same time, they are no means perfect, the erosion of the paint revealing original sketch lines, corrections, and gridlines. There is a liveliness to the innovative composition, tightly interweaving figures to produce both movement and a wonderful sense of harmony. While many of the images are standard scenes that had been appearing in tombs for hundreds of years, the artists managed to breathe fresh life into them, in ways never seen before in Egyptian art.

In the course of their conservation and examination, wonderful details were newly noted that had somehow never been observed before since the paintings arrived at the British Museum 190 years ago, such as the real gold used on the cat’s eye and the green paint on the left-hand side of the garden scene that can be reconstructed as a large sycomore fig tree.

The value of the paintings lies not only in their artistic merit though, but also in what they can tell us about Egyptian life. The gallery isn’t solely devoted to the paintings of the tomb chapel of Nebamun. Under the curatorship of Dr. Richard Parkinson, objects that further illuminate the lives of the people illustrated in the paintings have been woven into the gallery to infuse our understanding of the idealized Egyptian life depicted in the paintings with details of the realities. You can see the colourful painting materials and slightly unwieldy-looking brushes with which the artists worked their magic, as well as the possessions of both the rich and the poor, from fishing nets to board games to dazzling jewellery.

It was very interesting to see the process of choosing the objects to be displayed go through various stages of selection and whittling down. Like most museums, the British Museum can only display a fraction of their collections, partially due to space limitations and repetition of objects, but also because there is a delicate balance to be achieved in what is useful to furthering visitors’ knowledge and how much they can absorb. While it would be nice to include as many objects as possible, cluttering a small space might mean that people miss seeing key artifacts and lose sight of the message the gallery is trying to convey. It’s not just a desire for clarity that can be restrictive though, there is also consideration of the preservation of the objects. The most impressive object that didn’t make it into the final gallery was a magnificent finely-woven linen tunic, which would have needed such low lighting to preserve it from further degradation that you wouldn’t have been able to see the rest of the objects!

One of the other tasks I helped out with in preparation for the new gallery was a final desperate attempt to shed more light on the whereabouts of the lost tomb from which the paintings had been brutally removed so long ago. Although we know Nebamun’s tomb was located in Dra’ Abu el-Naga, we know little more. In vain, I scoured published archaeological records like Friederike Kampp’s survey of Theban tombs for any shred of evidence that might point to a known tomb being a potential location for Nebamun. While there were quite a few other Nebamuns buried in the area, all of them had details that ruled the BM’s Nebamun out. I wasn’t even able to identify a single tomb dated to the right era that was lacking any other defining information. There is a slim possibility that Nebamun’s tomb may still lie buried under further accumulations of debris, waiting to be rediscovered, but it may be so completely destroyed that it will forever remain unidentifiable.

The good news though is that now that the paintings have been restored and put on display again, Nebamun can be rediscovered by millions of people from around the world, and the gallery will breathe life once again into our understanding of the lives of the ancient Egyptians, who were so much more than just the sum of their statues and mummies.

Most people have heard the famous story about how Rameses the Great’s temple at

Most people have heard the famous story about how Rameses the Great’s temple at  was heavily influenced by their more famous neighbours, but yet was an important kingdom in its own right. Tragically, it comes at the cost of losing something we have only just begun to understand.

was heavily influenced by their more famous neighbours, but yet was an important kingdom in its own right. Tragically, it comes at the cost of losing something we have only just begun to understand.

Griffith are those of

Griffith are those of