Images courtesy of the Natural History Society of Northumbria, the Great North Museum: Hancock.

190 years ago today, on the 27th of September 1822, a young scholar delivered a paper just eight pages long and rather unassumingly titled ‘Letter to Monsieur Dacier’, but which would completely change the world’s understanding of ancient history. The scholar was Jean-François Champollion and his paper was the first truly significant breakthrough in the decipherment of hieroglyphs. By cracking a code that had defeated scholars for hundreds of years, he revealed the key to ancient Egypt’s secrets, opening up over three thousand years of history and one of the world’s oldest civilisations. After almost two millennia of relying on ancient Greek and Roman historians’ somewhat spotty understanding of the much older history of Egypt and the persistent misinterpretation of Egyptian writing as purely symbolic, with Champollion’s breakthrough the ancient Egyptians were finally able to speak for themselves. Champollion’s achievements were certainly the work of a genius but he also worked unbelievably hard, which probably contributed to his sudden death at age 42, and his great grammar and dictionary had to be published posthumously by his brother. Arguably the first Egyptologist, despite a relatively short career, he was already a hard act to follow.

Although the French scholar is famed for his work on the Rosetta Stone, the trilingual Egyptian inscription now in the British Museum, he was more interested in the insights it could offer than the text itself. In fact he never actually bothered to publish a full translation! When I began my work with the British Museum’s Future Curator programme, it was unsurprisingly that I got drawn into answering public enquiries about the Rosetta Stone and learning more about Champollion’s work. But I little expected to continue this research at the Great North Museum: Hancock in Newcastle upon Tyne, where I was posted for a year as part of the BM programme’s expertise sharing.

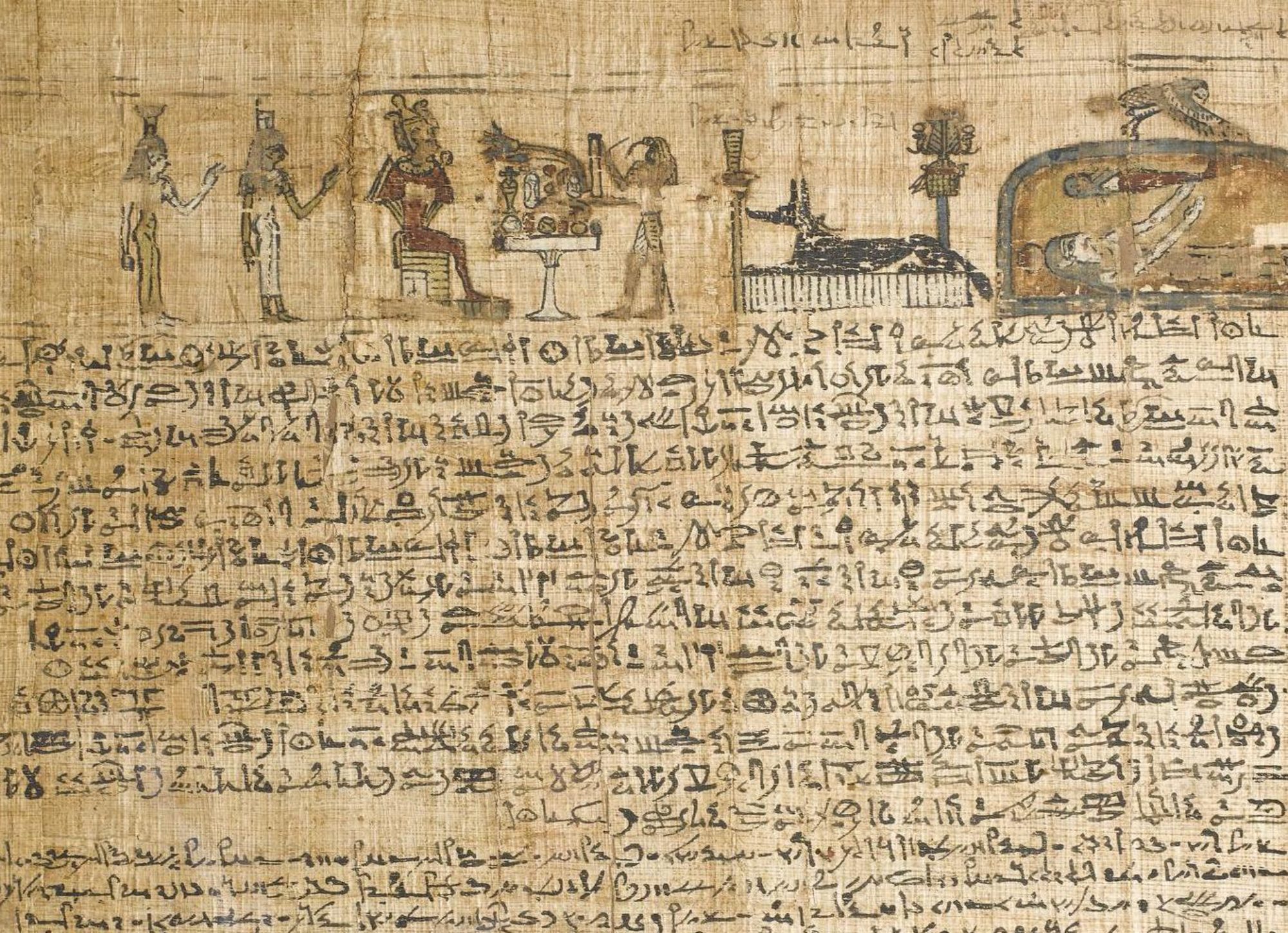

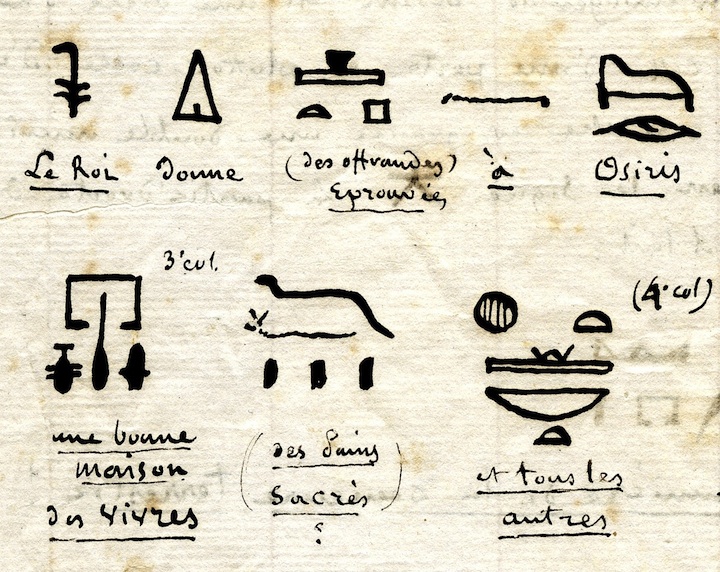

To my astonishment, the archivist there, June Holmes, casually mentioned that the museum had in its possession an incredibly rare letter written by Champollion, part of the Natural History Society of Northumbria’s Egyptian collection. I was astounded. Further investigation revealed an additional letter, though preserved only in copied translation, written even earlier, just one year after Champollion’s initial breakthrough, when his understanding of the ancient Egyptian language was still in its early stages. Object enquiries are now a routine part of museum work, so it was rather delightful to instead find the museum itself applying to someone else to interpret its objects! It was exhilarating to read Champollion’s sometimes faltering yet surprisingly confident and competent early work on one of the objects on display in the museum, the mummy of Bakt-en-Hor. Before Champollion was able to decipher the inscription, absolutely nothing was known about her and the usual stereotypical assumptions about her being a ‘princess’ abounded. Though he did not succeed in reading her name, his efforts gave the first real insights into her identity and beliefs.

Image courtesy of the Natural History Society of Northumbria, the Great North Museum: Hancock.

It was also just fascinating to read the words of the great man himself and find a rather different story to the generally accepted narrative of ‘the usual rivalry and animosity between the British and the French’ (Usick 2002, 77). Access to the Rosetta Stone and accurate copies of its inscription had been the source of some friction between Champollion and his English rival Thomas Young. When Champollion later failed to acknowledge a debt to Young’s early insights, his relationship with English scholars grew even frostier. The letters somewhat contradict this though, revealing a warm correspondence between the great man and the liberal scholarly community in the North East, which likely stemmed from a mutual interest in Egypt and shared political beliefs.

Newcastle was home to an enlightened scholarly community community at the time (the city’s Literary and Philosophical Society was host to the first public room to be lit by electric light, as well as many other scholarly achievements), as well as having rather radical political leanings towards social, political, and religious reform, including strong support for the French Revolution. The Champollions’ reformist ideals and dangerous support for Napoleon over the monarchy certainly adversely affected their careers. At the time, Champollion’s initial achievements were questioned, but the forward-thinking scholars of Newcastle upon Tyne embraced his breakthrough. The letters demonstrate that the inscription on the Great North Museum: Hancock’s mummy, Bakt-en-Hor, was amongst the earliest hieroglyphic texts read by Champollion, and offer new insights into the early process of his decipherment.

For Champollion, at a time when he had not yet been able to achieve his dream of travelling to Egypt, any hieroglyphic texts were precious and vital to his continuing progress with the script and language. As Richard Parkinson has stated, ‘The decipherment of the Egyptian scripts is not a single event that occurred in 1822, but a continuous process that is repeated at every reading of a text or artifact. Like any process of reading, it is a dialogue.’

Before leaving Newcastle next week at the end of my post, I wanted to seek a new dialogue by bringing those historic dialogues to light again- both Champollion’s dialogue with the ancient Egyptian language and with the scholars of Newcastle. On Thursday 4 October I will give a free lecture at the Great North Museum: Hancock to share my findings and honour the 190th anniversary of the decipherment. I will be presenting a work-in-progress, but I hope to finish this very soon and publish the letters. Many readers won’t be able to make it to the lecture, but to learn more about Champollion, I highly recommend Andrew Robinson’s recently published very readable and informative biography Cracking the Egyptian Code: The Revolutionary Life of Jean-Francois Champollion, and Richard Parkinson’s Cracking Codes: The Rosetta Stone and Decipherment, from the British Museum 1999 exhibition celebrating the bicentenary of the Stone’s discovery.